What I learned from looking at 900 most popular open source AI tools

https://huyenchip.com/2024/03/14/ai-oss.html

Mar 14, 2024 • Chip Huyen

[Hacker News discussion, LinkedIn discussion, Twitter thread]

Four years ago, I did an analysis of the open source ML ecosystem. Since then, the landscape has changed, so I revisited the topic. This time, I focused exclusively on the stack around foundation models.

The full list of open source AI repos is hosted at llama-police. The list is updated every 6 hours. You can also find most of them on my cool-llm-repos list on GitHub.

Data

I searched GitHub using the keywords gpt, llm, and generative ai. If AI feels so overwhelming right now, it’s because it is. There are 118K results for gpt alone.

To make my life easier, I limited my search to the repos with at least 500 stars. There were 590 results for llm, 531 for gpt, and 38 for generative ai. I also occasionally checked GitHub trending and social media for new repos.

After MANY hours, I found 896 repos. Of these, 51 are tutorials (e.g. dair-ai/Prompt-Engineering-Guide) and aggregated lists (e.g. f/awesome-chatgpt-prompts). While these tutorials and lists are helpful, I’m more interested in software. I still include them in the final list, but the analysis is done with the 845 software repositories.

It was a painful but rewarding process. It gave me a much better understanding of what people are working on, how incredibly collaborative the open source community is, and just how much China’s open source ecosystem diverges from the Western one.

Add missing repos

I undoubtedly missed a ton of repos. You can submit the missing repos here. The list will be automatically updated every day.

Feel free to submit the repos with less than 500 stars. I’ll continue tracking them and add them to the list when they reach 500 stars!

The New AI Stack

I think of the AI stack as consisting of 3 layers: infrastructure, model development, and application development.

- InfrastructureAt the bottom is the stack is infrastructure, which includes toolings for serving (vllm, NVIDIA’s Triton), compute management (skypilot), vector search and database (faiss, milvus, qdrant, lancedb), ….

- Model developmentThis layer provides toolings for developing models, including frameworks for modeling & training (transformers, pytorch, DeepSpeed), inference optimization (ggml, openai/triton), dataset engineering, evaluation, ….. Anything that involves changing a model’s weights happens in this layer, including finetuning.

- Application development With readily available models, anyone can develop applications on top of them. This is the layer that has seen the most actions in the last 2 years and is still rapidly evolving. This layer is also known as AI engineering.Application development involves prompt engineering, RAG, AI interface, …

Outside of these 3 layers, I also have two other categories:

- Model repos, which are created by companies and researchers to share the code associated with their models. Examples of repos in this category are

CompVis/stable-diffusion,openai/whisper, andfacebookresearch/llama. - Applications built on top of existing models. The most popular types of applications are coding, workflow automation, information aggregation, …

Note: In an older version of this post, Applications was included as another layer in the stack.

AI stack over time

I plotted the cumulative number of repos in each category month-over-month. There was an explosion of new toolings in 2023, after the introduction of Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT. The curve seems to flatten in September 2023 because of three potential reasons.

- I only include repos with at least 500 stars in my analysis, and it takes time for repos to gather these many stars.

- Most low-hanging fruits have been picked. What is left takes more effort to build, hence fewer people can build them.

- People have realized that it’s hard to be competitive in the generative AI space, so the excitement has calmed down. Anecdotally, in early 2023, all AI conversations I had with companies centered around gen AI, but the recent conversations are more grounded. Several even brought up scikit-learn. I’d like to revisit this in a few months to verify if it’s true.

In 2023, the layers that saw the highest increases were the applications and application development layers. The infrastructure layer saw a little bit of growth, but it was far from the level of growth seen in other layers.

Applications

Not surprisingly, the most popular types of applications are coding, bots (e.g. role-playing, WhatsApp bots, Slack bots), and information aggregation (e.g. “let’s connect this to our Slack and ask it to summarize the messages each day”).

AI engineering

2023 was the year of AI engineering. Since many of them are similar, it’s hard to categorize the tools. I currently put them into the following categories: prompt engineering, AI interface, Agent, and AI engineering (AIE) framework.

Prompt engineering goes way beyond fiddling with prompts to cover things like constrained sampling (structured outputs), long-term memory management, prompt testing & evaluation, etc.

AI interface provides an interface for your end users to interact with your AI application. This is the category I’m the most excited about. Some of the interfaces that are gaining popularity are:

- Web and desktop apps.

- Browser extensions that let users quickly query AI models while browsing.

- Bots via chat apps like Slack, Discord, WeChat, and WhatsApp.

- Plugins that let developers embed AI applications to applications like VSCode, Shopify, and Microsoft Offices. The plugin approach is common for AI applications that can use tools to complete complex tasks (agents).

AIE framework is a catch-all term for all platforms that help you develop AI applications. Many of them are built around RAG, but many also provide other toolings such as monitoring, evaluation, etc.

Agent is a weird category, as many agent toolings are just sophisticated prompt engineering with potentially constrained generation (e.g. the model can only output the predetermined action) and plugin integration (e.g. to let the agent use tools).

Model development

Pre-ChatGPT, the AI stack was dominated by model development. Model development’s biggest growth in 2023 came from increasing interest in inference optimization, evaluation, and parameter-efficient finetuning (which is grouped under Modeling & training).

Inference optimization has always been important, but the scale of foundation models today makes it crucial for latency and cost. The core approaches for optimization remain the same (quantization, low-ranked factorization, pruning, distillation), but many new techniques have been developed especially for the transformer architecture and the new generation of hardware. For example, in 2020, 16-bit quantization was considered state-of-the-art. Today, we’re seeing 2-bit quantization and even lower than 2-bit.

Similarly, evaluation has always been essential, but with many people today treating models as blackboxes, evaluation has become even more so. There are many new evaluation benchmarks and evaluation methods, such as comparative evaluation (see Chatbot Arena) and AI-as-a-judge.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure is about managing data, compute, and toolings for serving, monitoring, and other platform work. Despite all the changes that generative AI brought, the open source AI infrastructure layer remained more or less the same. This could also be because infrastructure products are typically not open sourced.

The newest category in this layer is vector database with companies like Qdrant, Pinecone, and LanceDB. However, many argue this shouldn’t be a category at all. Vector search has been around for a long time. Instead of building new databases just for vector search, existing database companies like DataStax and Redis are bringing vector search into where the data already is.

Open source AI developers

Open source software, like many things, follows the long tail distribution. A handful of accounts control a large portion of the repos.

One-person billion-dollar companies?

845 repos are hosted on 594 unique GitHub accounts. There are 20 accounts with at least 4 repos. These top 20 accounts host 195 of the repos, or 23% of all the repos on the list. These 195 repos have gained a total of 1,650,000 stars.

On Github, an account can be either an organization or an individual. 19/20 of the top accounts are organizations. Of those, 3 belong to Google: google-research, google, tensorflow.

The only individual account in these top 20 accounts is lucidrains. Among the top 20 accounts with the most number of stars (counting only gen AI repos), 4 are individual accounts:

- lucidrains (Phil Wang): who can implement state-of-the-art models insanely fast.

- ggerganov (Georgi Gerganov): an optimization god who comes from a physics background.

- Illyasviel (Lyumin Zhang): creator of Foocus and ControlNet who’s currently a Stanford PhD.

- xtekky: a full-stack developer who created gpt4free.

Unsurprisingly, the lower we go in the stack, the harder it is for individuals to build. Software in the infrastructure layer is the least likely to be started and hosted by individual accounts, whereas more than half of the applications are hosted by individuals.

Applications started by individuals, on average, have gained more stars than applications started by organizations. Several people have speculated that we’ll see many very valuable one-person companies (see Sam Altman’s interview and Reddit discussion). I think they might be right.

1 million commits

Over 20,000 developers have contributed to these 845 repos. In total, they’ve made almost a million contributions!

Among them, the 50 most active developers have made over 100,000 commits, averaging over 2,000 commits each. See the full list of the top 50 most active open source developers here.

The growing China’s open source ecosystem

It’s been known for a long time that China’s AI ecosystem has diverged from the US (I also mentioned that in a 2020 blog post). At that time, I was under the impression that GitHub wasn’t widely used in China, and my view back then was perhaps colored by China’s 2013 ban on GitHub.

However, this impression is no longer true. There are many, many popular AI repos on GitHub targeting Chinese audiences, such that their descriptions are written in Chinese. There are repos for models developed for Chinese or Chinese + English, such as Qwen, ChatGLM3, Chinese-LLaMA.

While in the US, many research labs have moved away from the RNN architecture for language models, the RNN-based model family RWKV is still popular.

There are also AI engineering tools providing ways to integrate AI models into products popular in China like WeChat, QQ, DingTalk, etc. Many popular prompt engineering tools also have mirrors in Chinese.

Among the top 20 accounts on GitHub, 6 originated in China:

- THUDM: Knowledge Engineering Group (KEG) & Data Mining at Tsinghua University.

- OpenGVLab: General Vision team of Shanghai AI Laboratory

- OpenBMB: Open Lab for Big Model Base, founded by ModelBest & the NLP group at Tsinghua University.

- InternLM: from Shanghai AI Laboratory.

- OpenMMLab: from The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- QwenLM: Alibaba’s AI lab, which publishes the Qwen model family.

Live fast, die young

One pattern that I saw last year is that many repos quickly gained a massive amount of eyeballs, then quickly died down. Some of my friends call this the “hype curve”. Out of these 845 repos with at least 500 GitHub stars, 158 repos (18.8%) haven’t gained any new stars in the last 24 hours, and 37 repos (4.5%) haven’t gained any new stars in the last week.

Here are examples of the growth trajectory of two of such repos compared to the growth curve of two more sustained software. Even though these two examples shown here are no longer used, I think they were valuable in showing the community what was possible, and it was cool that the authors were able to get things out so fast.

My personal favorite ideas

So many cool ideas are being developed by the community. Here are some of my favorites.

- Batch inference optimization: FlexGen, llama.cpp

- Faster decoder with techniques such as Medusa, LookaheadDecoding

- Model merging: mergekit

- Constrained sampling: outlines, guidance, SGLang

- Seemingly niche tools that solve one problem really well, such as einops and safetensors.

Conclusion

Even though I included only 845 repos in my analysis, I went through several thousands of repos. I found this helpful for me to get a big-picture view of the seemingly overwhelming AI ecosystem. I hope the list is useful for you too. Please do let me know what repos I’m missing, and I’ll add them to the list!

another article

What I learned from looking at 200 machine learning tools

Jun 22, 2020 • Chip Huyen

[Twitter thread, Hacker News discussion]

Click here to see the new version of this list with an interactive chart (updated December 30, 2020).

To better understand the landscape of available tools for machine learning production, I decided to look up every AI/ML tool I could find. The resources I used include:

- Full stack deep learning

- LF AI Foundation landscape

- AI Data Landscape

- Various lists of top AI startups by the media

- Responses to my tweet and LinkedIn post

- People (friends, strangers, VCs) share with me their lists

After filtering out applications companies (e.g. companies that use ML to provide business analytics), tools that aren’t being actively developed, and tools that nobody uses, I got 202 tools. See the full list. Please let me know if there are tools you think I should include but aren’t on the list yet!

Disclaimer

- This list was made in November 2019, and the market must have changed in the last 6 months.

- Some tech companies just have a set of tools so large that I can’t enumerate them all. For example, Amazon Web Services offer over 165 fully featured services.

- There are many stealth startups that I’m not aware of, and many that died before I heard of them.

This post consists of 6 parts:

I. Overview

II. The landscape over time

III. The landscape is under-developed

IV. Problems facing MLOps

V. Open source and open-core

VI. Conclusion

I. Overview

In one way to generalize the ML production flow that I agreed with, it consists of 4 steps:

- Project setup

- Data pipeline

- Modeling & training

- Serving

I categorize the tools based on which step of the workflow that it supports. I don’t include Project setup since it requires project management tools, not ML tools. This isn’t always straightforward since one tool might help with more than one step. Their ambiguous descriptions don’t make it any easier: “we push the limits of data science”, “transforming AI projects into real-world business outcomes”, “allows data to move freely, like the air you breathe”, and my personal favorite: “we lived and breathed data science”.

I put the tools that cover more than one step of the pipeline into the category that they are best known for. If they’re known for multiple categories, I put them in the All-in-one category. I also include the Infrastructure category to include companies that provide infrastructure for training and storage. Most of these are Cloud providers.

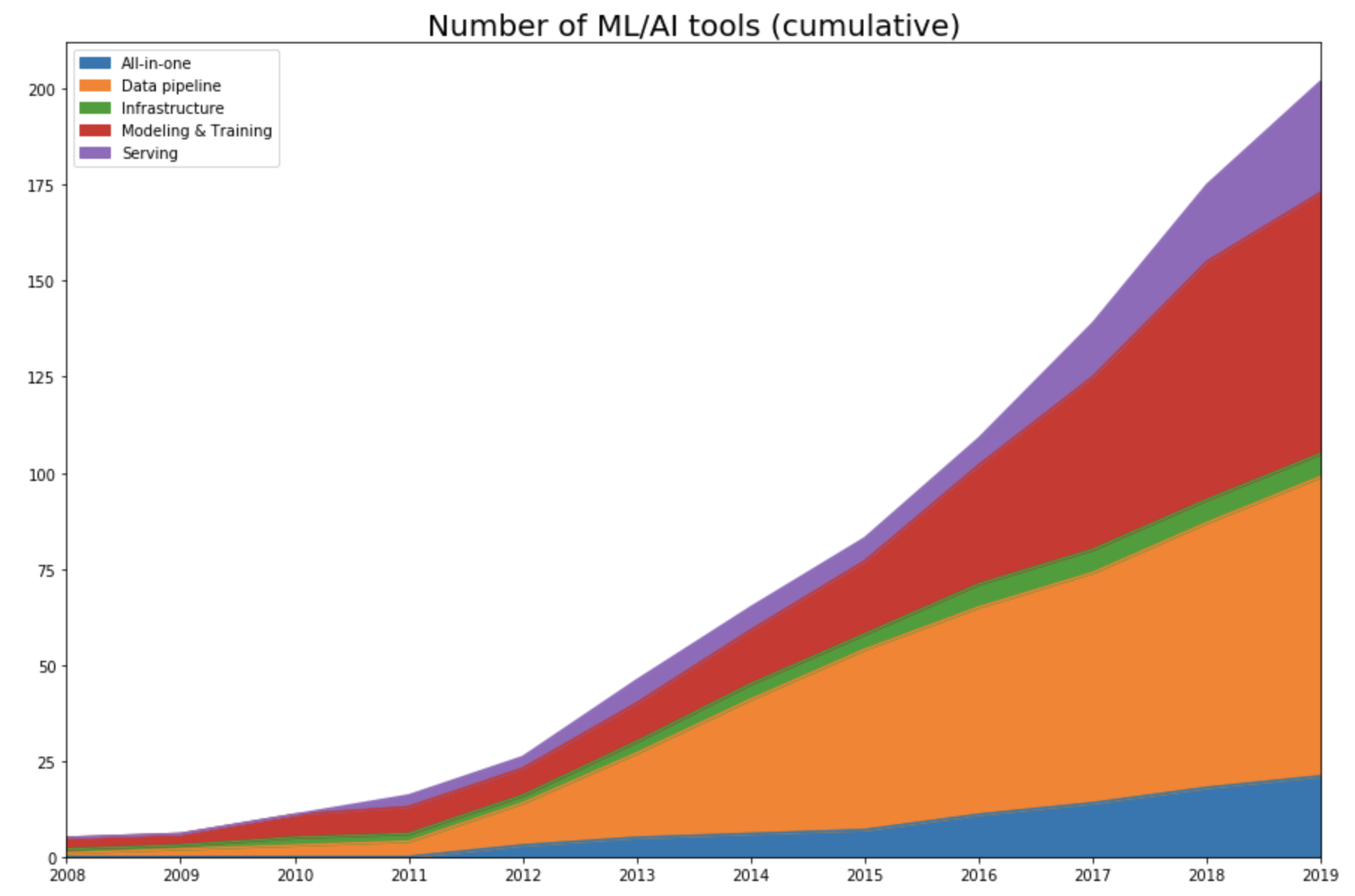

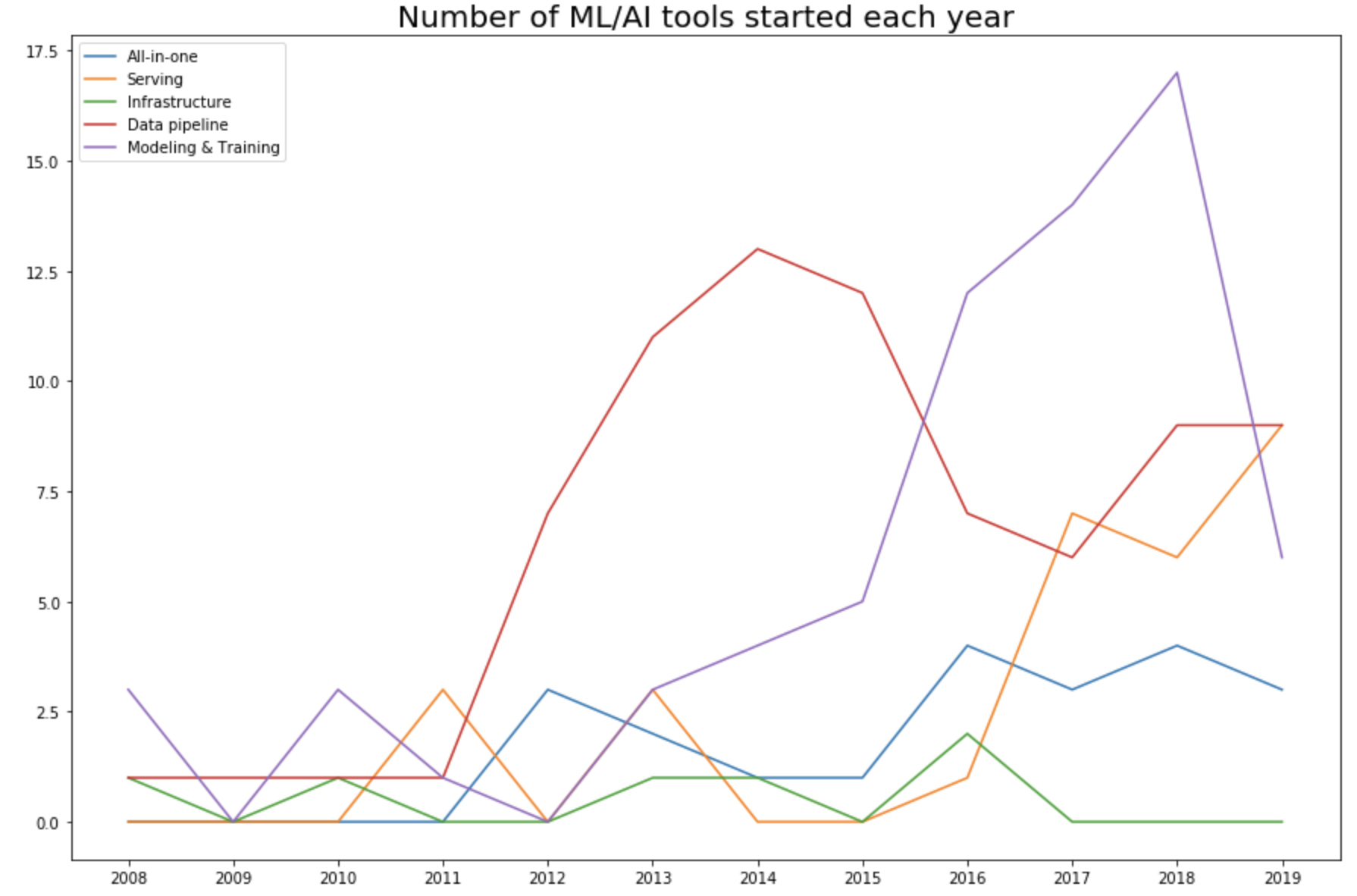

II. The landscape over time

I tracked the year each tool was launched. If it’s an open-source project, I looked at the first commit to see when the project began its public appearance. If it’s a company, I looked at the year it started on Crunchbase. Then I plotted the number of tools in each category over time.

As expected, this data shows that the space only started exploding in 2012 with the renewed interest in deep learning.

Pre-AlexNet (pre-2012)

Up until 2011, the space is dominated by tools for modeling and training, with some frameworks that either are still very popular (e.g. scikit-learn) or left influence on current frameworks (Theano). A few ML tools that started pre-2012 and survived until today have either had their IPOs (Cloudera, Datadog, Alteryx), been acquired (Figure Eight), or become popular open-source projects actively developed by the community (Spark, Flink, Kafka).

Development phase (2012-2015)

As the machine learning community took the “let’s throw data at it” approach, the ML space became the data space. This is even more clear when we look into the number of tools started each year in each category. In 2015, 57% (47 out of 82 tools) are data pipeline tools.

Production phase (2016-now)

While it’s important to pursue pure research, most companies can’t afford it unless it leads to short-term business applications. As ML research, data, and off-the-shelf models become more accessible, more people and organizations would want to find applications for them, which increases the demand for tools to help productionize machine learning.

In 2016, Google announced its use of neural machine translation to improve Google Translate, marking the one of the first major applications of deep learning in the real world. Since then, many tools have been developed to facilitate serving ML applications.

III. The landscape is under-developed

While there are many AI startups, most of them are application startups (providing applications such as business analytics or customer support) instead of tooling startups (creating tools to help other companies build their own applications). Or in VC terms, most startups are vertical AI. Among Forbes 50 AI startups in 2019, only 7 companies are tooling companies.

Applications are easier to sell, since you can go to a company and say: “We can automate half of your customer support effort.” Tools take longer to sell but can have a larger impact since you’re not targeting a single application but a part of the ecosystem. Many companies can coexist providing the same application, but for a part of the process, usually a selected few tools can coexist.

After extensive search, I could only find ~200 AI tools, which is puny compared to the number of traditional software engineering tools. If you want testing for traditional Python application development, you can find at least 20 tools within 2 minutes of googling. If you want testing for machine learning models, there’s none.

IV. Problems facing MLOps

Many traditional software engineering tools can be used to develop and serve machine learning applications. However, many challenges are unique to ML applications and require their own tools.

In traditional SWE, coding is the hard part, whereas in ML, coding is a small part of the battle. Developing a new model that can provide significant performance improvements in real world tasks is very hard and very costly. Most companies won’t focus on developing ML models but will use an off-the-shelf model, e.g. “if you want it put a BERT on it.”

For ML, applications developed with the most/best data win. Instead of focusing on improving deep learning algorithms, most companies will focus on improving their data. Because data can change quickly, ML applications need faster development and deployment cycles. In many cases, you might have to deploy a new model every night.

The size of ML algorithms is also a problem. The pretrained large BERT model has 340M parameters and is 1.35GB. Even if it can fit on a consumer device (e.g. your phone), the time it takes for BERT to run inference on a new sample makes it useless for many real world applications. For example, an autocompletion model is useless if the time it takes to suggest the next character is longer than the time it takes for you to type.

Git does versioning by comparing differences line by line and therefore works well for most traditional software engineering programs. However, it’s not suitable for versioning datasets or model checkpoints. Pandas works well for most traditional dataframe manipulation, but doesn’t work on GPUs.

Row-based data formats like CSV work well for applications using less data. However, if your samples have many features and you only want to use a subset of them, using row-based data formats still requires you to load all features. Columnar file formats like PARQUET and OCR are optimized for that use case.

Some of the problems facing ML applications development:

- Monitoring: How to know that your data distribution has shifted and you need to retrain your model? Example: Dessa, supported by Alex Krizhevsky from AlexNet and acquired by Square in Feb 2020.

- Data labeling: How to quickly label the new data or re-label the existing data for the new model? Example: Snorkel.

- CI/CD test: How to run tests to make sure your model still works as expected after each change, since you can’t spend days waiting for it to train and converge? Example: Argo.

- Deployment: How to package and deploy a new model or replace an existing model? Example: OctoML.

- Model compression: How to compress an ML model to fit in consumer devices? Example: Xnor.ai, a startup spun out of Allen Institute to focus on model compression, raised $14.6M at the valuation of $62M in May 2018. In January 2020, Apple bought it for ~$200M and shut down its website.

- Inference Optimization: How to speed up inference time for your models? Can we fuse operations together? Can we use lower precision? Making a model smaller might make its inference faster. Example: TensorRT.

- Edge device: Hardware designed to run ML algorithms fast and cheap. Example: Coral SOM.

- Privacy: How to use user data to train your models while preserving their privacy? How to make your process GDPR-compliant? Example: PySyft.

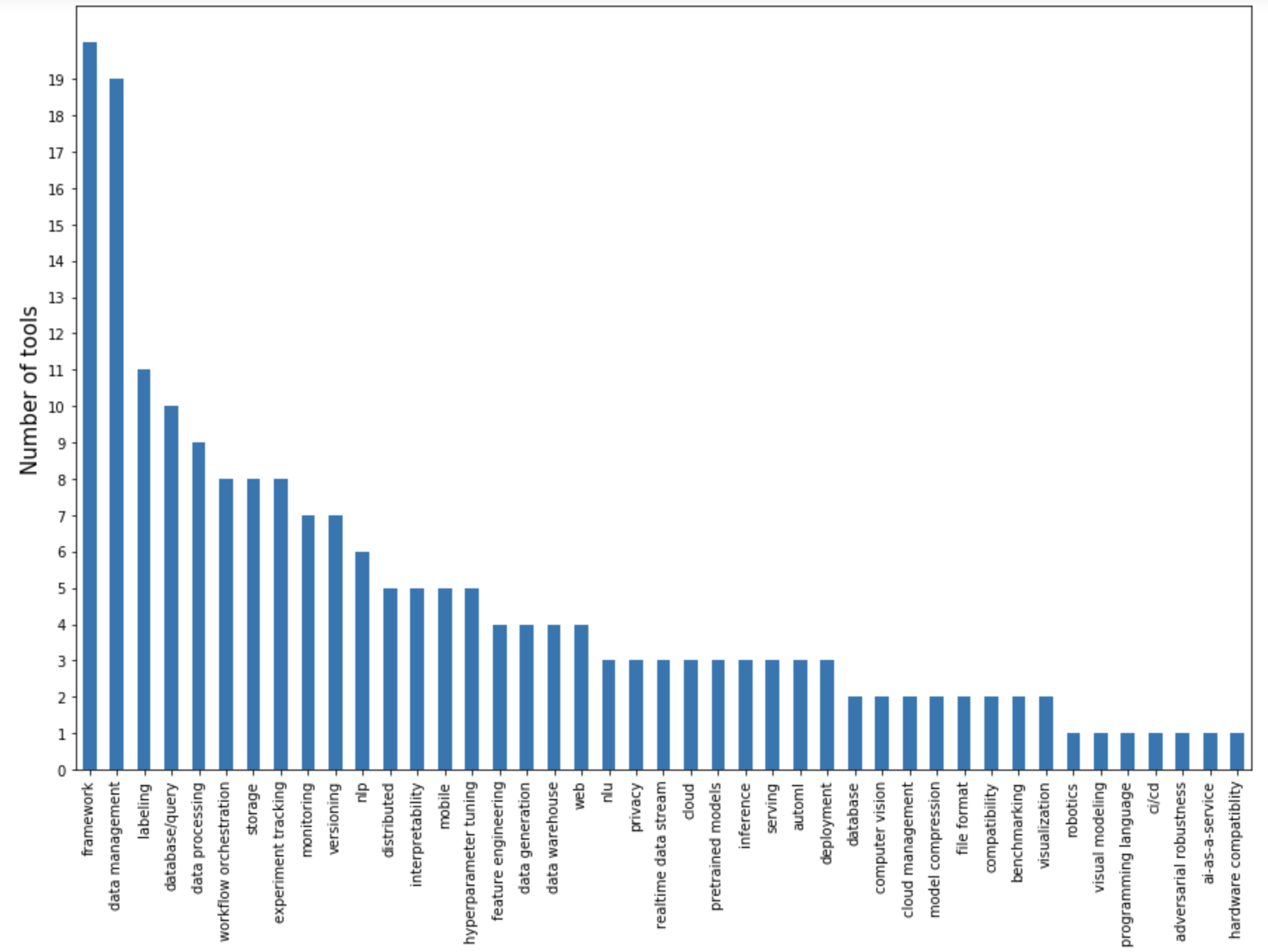

I plotted the number of tools by the main problems they address.

A large portion focuses on the data pipeline: data management, labeling, database/query, data processing, data generation. Data pipeline tools are also likely to aim to be all-in-one platforms. Because data handling is the most resource-intensive phase of a project, once you’ve had people put their data on your platform, it’s tempting to provide them with a couple of pre-built/pre-trained models.

Tools for modeling & training are mostly frameworks. The deep learning frameworks competition cooled down to be mostly between PyTorch and TensorFlow, and higher-level frameworks that wrap around these two for specific families of tasks such as NLP, NLU, and multimodal problems. There are frameworks for distributed training. There’s also this new framework coming out of Google that every Googler who hates TensorFlow has been raving about: JAX.

There are standalone tools for experiment tracking, and popular frameworks also have their own experiment tracking features built-in. Hyperparameter tuning is important and it’s not surprising to find several that focus on it, but none seems to catch on because the bottleneck for hyperparameter tuning is not the setup, but the computing power needed to run it.

The most exciting problems yet to be solved are in the deployment and serving space. One reason for the lack of serving solutions is the lack of communication between researchers and production engineers. At companies that can afford to pursue AI research (e.g. big companies), the research team is separated from the deployment team, and the two teams only communicate via the p-managers: product managers, program managers, project managers. Small companies, whose employees can see the entire stack, are constrained by their immediate product needs. Only a few startups, usually those founded by accomplished researchers with enough funding to hire accomplished engineers, have managed to bridge the gap. These startups are poised to take a big chunk of the AI tooling market.

V. Open-source and open-core

109 out of 202 tools I looked at are OSS. Even tools that aren’t open-source are usually accompanied by open-source tools.

There are several reasons for OSS. One is the reason that all pro-OSS people have been talking about for years: transparency, collaboration, flexibility, and it just seems like the moral thing to do. Clients might not want to use a new tool without being able to see its source code. Otherwise, if that tool gets shut down – which happens a lot with startups – they’ll have to rewrite their code.

OSS means neither non-profit nor free. OSS maintenance is time-consuming and expensive. The size of the TensorFlow team is rumored to be close to 1000. Companies don’t offer OSS tools without business objectives in mind, e.g. if more people use their OSS tools, more people know about them, trust their technical expertise, and might buy their proprietary tools and want to join their teams.

Google might want to popularize their tools so that people use their cloud services. NVIDIA maintains cuDF (and previously dask) so that they can sell more GPUs. Databricks offers MLflow for free but sells their data analytics platform. Netflix started their dedicated machine learning team very recently, and released their Metaflow framework to put their name on the ML map to attract talents. Explosion offers SpaCy for free but charges for Prodigy. HuggingFace offers transformers for free and I have no idea how they make money.

Since OSS has become a standard, it’s challenging for startups to figure out a business model that works. Any tooling company started has to compete with existing open-source tools. If you follow the open-core business model, you have to decide which features to include in the OSS, which to include in the paid version without appearing greedy, or how to get free users to start paying.

VI. Conclusion

There has been a lot of talk on whether the AI bubble will burst. A large portion of AI investment is in self-driving cars, and as fully autonomous vehicles are still far from being a commodity, some hypothesize that investors will lose hope in AI altogether. Google has freezed hiring for ML researchers. Uber laid off the research half of their AI team. Both decisions were made pre-covid. There’s rumor that due to a large number of people taking ML courses, there will be far more people with ML skills than ML jobs.

Is it still a good time to get into ML? I believe that the AI hype is real and at some point, it has to calm down. That point might have already happened. However, I don’t believe that ML will disappear. There might be fewer companies that can afford to do ML research, but there will be no shortage of companies that need tooling to bring ML into their production.

If you have to choose between engineering and ML, choose engineering. It’s easier for great engineers to pick up ML knowledge, but it’s a lot harder for ML experts to become great engineers. If you become an engineer who builds great tools for ML, I’d forever be in your debt.

Acknowledgment: Thanks Andrey Kurenkov for being the most generous editor one could ask for. Thanks Luke Metz for being a wonderful first reader.

I want to devote a lot of my time to learning. I’m hoping to find a group of people with similar interests and learn together. Here are some of the topics that I want to learn:

- How to bring machine learning to browsers

- Online predictions and online learning for machine learning

- MLOps in general

If you want to learn any of the above topics, join our Discord chat. We’ll be sharing learning resources and strategies. We might even host learning sessions and discussions if there’s interest. Serious learners only!